I’ve been exploring STORY a bit in the last few weeks, and here I’d like to focus on the stories we tell others. Dragging along from last week is the stories we tell ourselves–and those, to a certain degree, shape the stories we tell others. There’s a whole lot of other things rattling in my head as well: Terry Pratchett’s new book, Dodger, The Story (a chronological account of the Bible), and Significant Objects. In a way, the stories we tell others are a form of world-building. We include details that fit within the parameters of the world we wish to create. We ignore the ones that don’t.

Life is a rich and complex interweaving of inner and outer stories. Here are a few threads that seem to run throughout.

1. We tell others stories based on our perspective of the truth.

I just finished the book Dodger by Terry Pratchett, and in the book (a historical fantasy according to the author’s note at the end) Charles Dickens explains to Dodger how truth is a fog. This explanation comes after Dodger’s encounter with the mad barber Sweeney Todd. Dodger is hailed as a hero, but he dislikes the description because Sweeney Todd “wasn’t bad, he was mad, and sad, and lost in his ‘ead.”[ ] “I mean, I ain’t no hero, ‘cos I don’t think he was a villain, sir, if you get my drift.” Charlie then explains how truth is anything but simple because it all depends on perspective. “Truth is a fog, in which one man sees the heavenly host and the other one sees a flying elephant.”

Think about eye-witnesses. Every single one sees a different accident because every one of them sees it from a different perspective. That’s part of what makes eye-witnesses so terribly unreliable.

So what does this mean for your writing? First off, it’s a great way to develop character. Second, who you choose to be the narrator determines the story. Sometimes people go with more than one narrator for that very reason. And finally, think about how aware (or not) your character is about their and others’ bias in perspective. What do they do when something challenges their “world?” How close does their story stick to the facts? Reliable narrator or unreliable narrator.

2. We tell others the stories we want them to hear. This, of course, involves not only what we say, but maybe even more importantly, what we don’t say. A lot of our self-esteem is tied up in what other people think of us, and so it makes sense that we–both consciously and unconsciously–try to shape that image with the stories we share. If I want people to think I’m strong and practical, I might not want to share how I got all teary-eyed when the cat died in the Ramona and Beezus movie I was watching with my daughters.

This summer I got a bit bogged down in how to start the story I was working on. Mind you, I’d already written several different beginnings, but I wanted to use the “best” one. I finally figured out how to start the novel when I remembered to “ask” Jane (the narrator) how she would tell the story. To make a story ring true, the author must always remember who is telling that story. What would that character share or keep secret?

On the flip side, sometimes people hear what they want to hear–no matter what they are told. Terry Pratchett (being a master writer) uses this in his book, Dodger. The main character tells the crowd that he didn’t fight off the terrible villain Mister Sweeney Todd, but it doesn’t matter. The people are sure Dodger is a hero who valiantly fought off a savage murderer. That, after all, is a much more interesting story than carefully disarming a war veteran who is in the midst of a post-tramatic stress flashback.

3. We tell stories we think our audience can understand and relate to.

I’ve worked with 7th and 8th graders for many years now, but still find myself talking over their heads. All those blank looks, and I know I need to change my story into something easier. Think about it, the story you tell about where babies come from changes depending on whether you are talking to a 7-year-old or a 13-year-old. (And, for those twenty to sixty ((and above)) you might get something like Fifty Shades of Grey)

On a less physical note, I was thinking about this idea of story and audience at church where we are reading through The Story, which is the Bible put in chronological order. As we study each chapter, the pastor makes a point of talking about the Upper Story and the Lower Story. The Upper Story is what God is doing to bring about His plan of salvation. The Lower Story is all the daily lives and dramas of the Israelites–and us. So maybe God tells the story of salvation through the daily dramas because that is what we can understand. Think of myths. Zeus with his thunderbolts was something the people of the time could understand and picture. Could it be that when the Bible was written, the earth being created in six days was understandable, whereas millions of years of change was not so understandable.

In your writing — How do your characters shape their stories based on audience? And of course, some of the conflict comes in the misunderstanding between characters, so maybe your characters don’t understand each other’s stories.

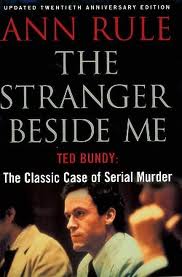

4. Stories give value.

The book, Significant Objects, talks about a study where authors were hired to write a story about an object and then sell that object online along with the story. The results of the study showed that a good story made an object more valuable. I thought a lot about this. It seems to hold true to more than just objects. Think about people. So easy to stereotype–until you get to know an individual’s stories. That is when we start to see them as a person of value, maybe because so often our stories share common elements. In each story, we can see a small reflection of ourself.

And finally,

5. The stories we share with others either let people in, expanding their world and ours, or shut them out, locking us in. In your writing, do you (and your characters) shut doors or open them? Something to ponder as you build words and worlds.

world and ours, or shut them out, locking us in. In your writing, do you (and your characters) shut doors or open them? Something to ponder as you build words and worlds.