Time Flies

Spring Break is almost done–and of course I had way more things I planned to do than could actually be done in the amount of time. Still, I slept, read a few good books, painted a little, visited relatives, and ate some good food. (Greg is barbecuing ribs ribs right now. What with his jalapeno potato salad it makes for a fabulous last supper.) Notice what isn’t on the list. No writing. Well, until now. Nothing like a deadline to get one inspired!

The work week is scheduled to start with a bang–5 classes of book talks. All on the

Classics

Classics. So is it possible to get today’s kids interested enough to sit and work their way through Stevenson, Twain, Bronte, Alcott, or Jack Schaefer? I LOVED Shane. My dad read it aloud to us when I was in 5th or 6th grade. But we didn’t even have a television growing up, much less the internet or Wii, or Xbox or Netflix. After dinner my dad would read to me and my brother and sisters. I have fond memories of listening to Robinson Crusoe, Swiss Family Robinson (My brother and I played cast away in the woods by our house for several weeks after that one), Treasure Island, Huckleberry Finn, and Tom Sawyer. And of course, how could one not like the animal stories? The Yearling (how I cried), Sounder (cried again), Rascal, Incident at Hawks Hill (one of my favorites), The Incredible Journey, Lad: a dog (Why are all the dog stories sad?), The Call of the Wild (my daughter still hasn’t forgiven me for suggesting she read that one. She cried.), White Fang, Black Beauty, and of course, The Black Stallion.

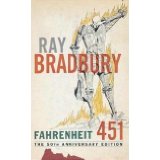

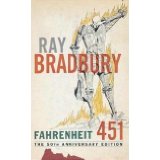

Fahrenheit 451

Despite all the classics my dad read to us, there were many that I didn’t read–even despite being an English major in college. I just read Slaughterhouse Five this past summer, and I’m reading A Prayer for Owen Meiny right now. And it just so happened that I read Fahrenheit 451 right when The Hunger Games had first come out. A very lucky coincidence for me, I do believe. Fahrenheit 451 is a book that I can’t get out of my mind. Dystopian fiction, just like The Hunger Games. The difference is … a matter of degree. Only a matter of degree. But it is the small matter of degree that makes Fahrenheit 451 that much scarier to me than The Hunger Games.

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury is a science fiction story set in a future (maybe not as

Burning books

future as we might wish, I might add) where everything is about being happy. Wall-sized televisions, radios that fit into a person’s ear, interactive shows–so much to keep people entertained, much like today. The main character, Guy Montag, is a fireman, and it’s his job to burn the books. Not that the government made reading illegal. Oh no. It was the PEOPLE who quit reading. It happened slowly. At first, it was this group or that group being offended by something this book or that book said. So writers had to make sure not to include anything that might be offensive–to anyone. And then there was the fact that people so busy, they didn’t want to take the time to read a whole book, so books became abridged, and then those become summarized, and finally, you could read the classics in what we would today call a “tweet version.” (Wouldn’t that be an interesting assignment? Write a tweet for each classic you’ve read)

Firemen

So really, the fireman’s job wasn’t even really necessary, it was about providing a show, entertaining the people. And Montag goes along with this unquestioning until he meets Clarisse. Clarisse is different. She talks about ideas, not things. She asks why instead of how. And that start Montag thinking. But thinking, like being different, is dangerous in this society. When an old woman chooses to burn to death along with her books, Montag hides one of the books under his jacket to find out what makes them so important. And when Clarisse disappears, Montag knows that it is only a matter of time before the firemen’s mechanical hound comes after him as well.

Dystopian Fiction is huge right now in the YA world. The Hunger Games started it, but now there is Legend, The Eleventh Plague, The Maze Runner, Epitaph Road, Blood Red Road, and Safekeeping–just to name a few. Why are teens so interested in reading such dark fiction? Why are so many writers writing dystopian fiction? (of course, the fact that it sells is part of it–but only a part. I’d argue that writers must still have a certain amount of interest in the subject to devote the time to writing it.) Maybe Bradbury and his book Fahrenheit 451 can give us some clues as to why this genre has become so popular in 2012-2013.

Bradbury published Fahrenheit 451 in 1953, shortly after WWII and during the McCarthy era of censorship. That, of course, plays a big role in the novel, and Bradbury admitted in an interview that it was this everyone being afraid of spies and their neighbors and censoring that led him to write Fahrenheit 451. As a librarian, I’m fascinated by the fact that Fire-Captian Beatty is the one who tells Montag that the end of reading came not from the government, but from the people. I read reports in the news declaring that Americans read less and less–but I’m never sure how much I believe those reports. In my own little corner of the world, I’d say students read about as much as they used to, possibly even more. A lot of book reading is now done on digital devices, but it is still reading. So did Beatty tell Montag that to cover up the government’s part in the matter?

The censorship issue is definitely still out there, whether it is the government, the corporations (thinking tobacco companies), or the people. According to the all-knowing (said with some irony) Wikipedia, Bradbury wrote a new coda for the book when the paperback edition was released in 1979. In it he makes several comments on censorship.

There is more than one way to burn a book. And the world is full of people running about with lit matches. Every minority, be it Baptist / Unitarian, Irish / Italian / Octogenarian / Zen Buddhist / Zionist / Seventh-day Adventist / Women’s Lib / Republican / Mattachine / FourSquareGospel feels it has the will, the right, the duty to douse the kerosene, light the fuse….Fire-Captain Beatty, in my novel Fahrenheit 451, described how the books were burned first by the minorities, each ripping a page or a paragraph from this book, then that, until the day came when the books were empty and the minds shut and the library closed forever. Only six weeks ago, I discovered that, over the years, some cubby-hole editors at Ballantine Books, fearful of contaminating the young, had, bit by bit, censored some 75 separate sections from the novel. Students, reading the novel which, after all, deals with the censorship and book-burning in the future, wrote to tell me of this exquisite irony. Judy-Lynn del Rey, one of the new Ballantine editors, is having the entire book reset and republished this summer with all the damns and hells back in place.[8]

The American Library Association keeps a list of frequently challenged books. It’s always interesting to me to look at the reason why people protest this book or that book. All one has to do nowadays to see how “bothered” or “intolerant” people can be to those who hold different viewpoints is go on YouTube or Facebook and read the comments people post. We seemed to have become a society that is incapable of disagreeing in a civil manner. Sports fans, political parties, all the rhetoric becomes more and more inflamed. Maybe it is easy to imagine the intolerance growing into censorship and then something even darker.

The other theme in Bradbury’s book is the role of mass media in the isolation and

Technology

alienation of people. Again, from Wikipedia:

“In the late 1950s, Bradbury observed that the novel touches on the alienation of people by media:

In writing the short novel Fahrenheit 451 I thought I was describing a world that might evolve in four or five decades. But only a few weeks ago, in Beverly Hills one night, a husband and wife passed me, walking their dog. I stood staring after them, absolutely stunned. The woman held in one hand a small cigarette-package-sized radio, its antenna quivering. From this sprang tiny copper wires which ended in a dainty cone plugged into her right ear. There she was, oblivious to man and dog, listening to far winds and whispers and soap-opera cries, sleep-walking, helped up and down curbs by a husband who might just as well not have been there. This was not fiction.[9]

In a 2007 interview, Bradbury stated that the book explored the effects of television and mass media on the reading of literature.[10] Bradbury went even further to elaborate his meaning, saying specifically that the culprit in Fahrenheit 451 is not the state—it is the people.”[10]

When Bradbury wrote Fahrenheit 451, colored tv had just been approved by the FCC in 1950. Videotape, remote controls all came out in the 50’s. Lots of changes in the world. And then there is now. Technology has changed the world–and it is doing so at an ever-increase rate. Go anywhere nowadays and you can see people sitting silent, side-by-side, texting away on their phones and ignoring everyone around them. The wall-sized televisions, the thousands of channels, the “reality” shows that are all about entertainment and not so much about reality. People have hundreds of “friends”, but are they more isolated than ever? According to The Atlantic and many other articles, some research seems to be saying so.

And then there was WWII and the fact that it had served to pull America out of its rather insular position in the world. Have the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan served to remind teens today that we are a part of a global society in which not everyone likes us? Does that play another part in what makes young people so fascinated with dystopian fiction? Does it help them imagine the worst so that the present doesn’t seem so bad? Or so that even if it gets that bad, there is still hope?

Whatever your thoughts on the matter, I think I will start by telling my students that classics are still worth reading today because they continue to offer us truths about human nature–and they are dang good stories.

Great stories

Oh, and when I went looking for a youtube video on Fahrenheit 451, I found one by the vlogbrothers–John and Hank Green. Love their videos (and John’s books too.)

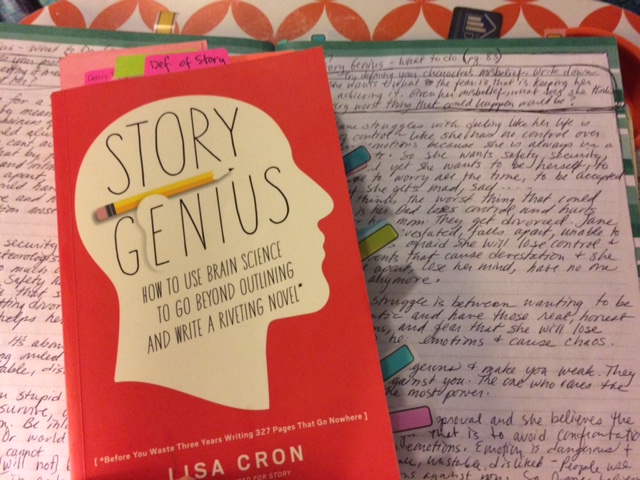

School’s out, which means I’m able to be more of a writer. This summer, as I revise my novel, I Feel For You, I’m studying how to be a story genius. The “textbook” I’m using is Story Genius: how to use brain science to go beyond outlining and write a riveting novel.

School’s out, which means I’m able to be more of a writer. This summer, as I revise my novel, I Feel For You, I’m studying how to be a story genius. The “textbook” I’m using is Story Genius: how to use brain science to go beyond outlining and write a riveting novel.  I’m revising, but it is still helpful for that as well. The shitty first draft has been written, but I knew I needed to ratchet up the tension. Unfortunately, I wasn’t exactly sure how. Working through Lisa Cron’s book allows me to pin-point WHY the lack of tension, the absence of urgency–and it is also helping me know how to build that urgency into my manuscript.

I’m revising, but it is still helpful for that as well. The shitty first draft has been written, but I knew I needed to ratchet up the tension. Unfortunately, I wasn’t exactly sure how. Working through Lisa Cron’s book allows me to pin-point WHY the lack of tension, the absence of urgency–and it is also helping me know how to build that urgency into my manuscript.