Utilizing setting to deepen your story

Last night I met with my writing group, and it brought home yet again why writing groups are so important. As a writer, I don’t always realize how much is in my head, but not on the page. My writing group is very good on pointing out what is missing–or what is leading them a down a different path than where I’d intended the reader to go.

In our group, the author reads her piece of writing while the others follow along on their own copy. Then the author sits back like a fly on the wall while the “readers” talk about the piece of writing. So last night after I read my scene, the very first comment went something like this: “I can’t see them–I mean, I can’t picture where the characters are–and that makes it difficult for me to visualize what they are doing.”

Oops, I did it again (to quote a popular but definitely not favorite song). I knew where the characters were, but I forgot to look around and describe it for my readers. The scene started with this sentence:

After school, we headed back to what I called the training room, having finished eating hummus and chips in the kitchen. Grandma Lange led us through the practice of Grounding, and I dutifully imagined roots growing into the floorboards beneath me…..

So okay, we have a time of day–after school–and we have a place–the training room. But that didn’t give my readers enough to see what the characters were doing. Were they sitting? If so, on what? Maybe they were standing–and if so, were they close to each other? Far apart? We can’t SEE them, and that makes what follows confusing.

Not only did my lack of description of the setting make the scene confusing, but I missed an opportunity to deepen the story.

So what can setting do for your story?

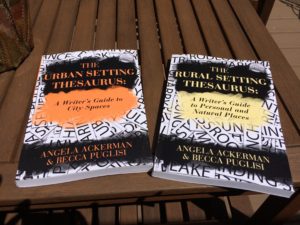

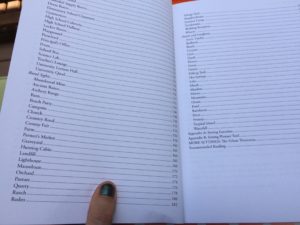

In The Urban Setting Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to City Space by Angela Ackerman & Becca Puglisi, setting is described as “a powerhouse of storytelling description that deepens every scene.” Not only does it root the reader in the events–or fail to do so, in my case–but it also, if chosen carefully, can “help characterize the story’s cast, deliver backstory in a way that enriches, covey emotion, supply tension, and accomplish a hot of other things to give readers a one-of-a-kind experience.” (p. 1)

In The Rural Setting Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Personal and Natural Places also by Angela Ackerman & Becca Puglisi, setting is described like this:

They’re places that hold meaning for the character and evoke emotion. They provide opportunities for conflict and personal tragedy and growth. As such, birthplaces, bedrooms, schools, workplaces, hangouts, and vacation spots play a pivotal role in shaping who a character is and who he will become. [ ] Written effectively, this emotional connection reaches out to include the reader too.”(p. 1)

Setting, done right, can help a writer:

- allow the reader to visualize/understand what is going on in the scene

- develop character

- provide backstory that both advances plot and/or develops character

- supply tension and/or a source of conflict

- convey tone/mood

Let’s look at another example where I think I did a better job making the most of my setting.

After bundling up in winter gear, I stepped into a blinding world. Wherever the sun struck the snow, it sparked a million different colors, like diamonds in the firelight. Wiping watering eyes with the back of a mitten, I headed down the street. My breath plumed out clouds, and the cold air stung the tip of my nose.

In the neighborhoods closer to Lake Michigan, the houses grew bigger. Not that the Williams lived in a mansion, but it doubled my house. The sidewalk ended, and I headed across the street to where it picked up again on the other side just past the entrance to the Lake Forest cemetery. A blanket of untouched snow covered the ground and tucked around the gray and black tombstones and mausoleums.

Once, I’d admitted to Eva that those little stone houses both creeped me out and fascinated me because I imagined someone opening the door and coming out.

Eva had rolled her eyes and said with mock chagrin, “Only you bleeding heart religious sorts believe in anyone coming out of the grave. Stick to scientific fact, you’ll sleep better, I promise. Cemeteries are a waste, just dead space. I plan to donate my body to science. My mom tells me it’s hard for the university medical program to get enough cadavers for student use.”

That’s Eva in a nutshell, I thought, turning to walk the rest of the way to her house. If she can’t test, slice, dice, or document it in some way—it doesn’t exist.

I’d like to think that in this passage, I used setting (the neighborhood and the graveyard) to do more than just help the reader visualize what is happening in the scene. The description of the houses in the neighborhood inform the reader that Eva’s family is richer than Jane’s family.

Having Jane walk past the graveyard allowed me to practice what Fleda Brown (a poet who was a speaker at a writing conference I attended) called going out from where you are. This means using something in the story (in this case, the mausoleums) to travel somewhere else–or some when else. Think about it–our memory often works by association. So a writer can provide backstory in a way that seems natural by using something a character sees, hears, smells, does, or tastes to trigger a memory. In my example, the sight of the mausoleums reminds Jane of a previous conversation she had with Eva.

Adding this bit of backstory triggered by the setting created (or at least, indicated) a source of tension, setting Jane’s view of the world against Eva’s. That tension hints at the larger conflict involving the struggle to accept that which cannot be scientifically proven.

Could my setting do even more? Maybe. I’ll keep working on making my settings multi-task. That’s the joy of re-writing.

Is your setting doing all that it could for your story?